A Trail Runner's Guide to Poison Oak

By Carl Arft

Running along Big Sur coast, a prime location for poison oak

Running along Big Sur coast, a prime location for poison oak (Image from runnersworld.com)

Ah, the joy of running along your favorite trail, enjoying the views, and minding your own business. You finish the run, then join your running buddies for dinner and some well-earned drinks. You're still riding your running high the next day until you notice a strange burning sensation in your legs. "Hmm, that's strange" you think to yourself as the burning becomes more intense during the day. By that evening, a red rash has started to develop and the itching keeps you up most of the night. By the next day, your legs are covered with patches of red bumps and blisters. "OH NO!! Poison oak!!" you moan to yourself, but at this point it's too late. Prepare yourself for a week of itching, burning misery.

As an avid trail runner and hiker who is also extremely allergic to poison oak, I've suffered from mild to severe rashes many times. A recent particularly bad case inspired me to do my own research on poison oak to determine the best ways to prevent and treat the painful, itchy rashes. This included a lot of online research, speaking with several doctors, and even using myself as a guinea pig to test certain treatments I found on the web. I discovered a lot of good and useful information, but also many opinions, misinformation, and rumors that are stated as facts but in actuality are misleading or harmful. In this article I attempt to distinguish the facts from fiction. Even if you think you know everything about poison oak, you still should read the last section titled Common poison oak myths... True or false?

Disclaimer: I am neither a medical doctor nor a trained botanist. As Dr. McCoy might say, "Dammit Jim, I'm an Engineer, not a Doctor!" However, in writing this article I have tried to reference information only from reputable journals, or websites of reputable universities and agencies, or Wikipedia pages that reference such reputable journals, universities, and agencies. In some cases, information in this article is based on my personal experiences and knowledge I have gained through trial and error, and I have tried to distinguish these clearly in the article. Any advice presented in this advice should be followed at your own risk. Always consult a medical doctor if you experience severe symptoms!

As an avid trail runner and hiker who is also extremely allergic to poison oak, I've suffered from mild to severe rashes many times. A recent particularly bad case inspired me to do my own research on poison oak to determine the best ways to prevent and treat the painful, itchy rashes. This included a lot of online research, speaking with several doctors, and even using myself as a guinea pig to test certain treatments I found on the web. I discovered a lot of good and useful information, but also many opinions, misinformation, and rumors that are stated as facts but in actuality are misleading or harmful. In this article I attempt to distinguish the facts from fiction. Even if you think you know everything about poison oak, you still should read the last section titled Common poison oak myths... True or false?

Disclaimer: I am neither a medical doctor nor a trained botanist. As Dr. McCoy might say, "Dammit Jim, I'm an Engineer, not a Doctor!" However, in writing this article I have tried to reference information only from reputable journals, or websites of reputable universities and agencies, or Wikipedia pages that reference such reputable journals, universities, and agencies. In some cases, information in this article is based on my personal experiences and knowledge I have gained through trial and error, and I have tried to distinguish these clearly in the article. Any advice presented in this advice should be followed at your own risk. Always consult a medical doctor if you experience severe symptoms!

Contents

Background: What is poison oak and why the hell does it exist?!

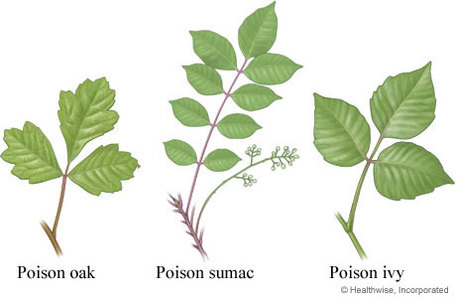

OK, so I haven't found a good answer to the question of "why the hell does poison oak exist?!" but I can give some background about poison oak. In nature, there are a variety of plants that can cause skin reactions when exposed to oils or chemicals that naturally occur in the plant. The most common skin reaction is caused by contact with the sap oil of plants in the genus Toxicodendron. In the United States, the most common members of this genus are poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. Interestingly, the common names for these plants are actually misnomers. Poison "oak" is not an oak, and poison "ivy" is not an ivy. Instead, these plants were named based on their resemblance to true oak and ivy [1]. In general, poison ivy grows east of the Rocky Mountains, poison oak west of the Rocky Mountains, and poison sumac in the southeastern United States.

|

The primary species of Toxicodendron that is found in California is poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum). Poison oak is native to western North America in an area extending from British Columbia to the Baja California peninsula. It is widespread and grows in a wide range of habitats at elevations ranging from sea level to about 5,000 feet, and in areas including open woodland, grassy hillsides, coniferous forests, and open chaparral [2].

Poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac all contain an oil called urushiol, pronounced "oo-ROO-shee-ohl". The plants release the oil when the leaf or other plant parts are bruised, damaged, or burned. When the oil gets on the skin, an allergic reaction, referred to as contact dermatitis, occurs in most people as an itchy red rash with bumps or blisters. When exposed to 50 micrograms of urushiol (an amount less than one grain of table salt) 80 to 90 percent of adults will develop a rash [3]. However, people vary greatly in their sensitivity to urushiol. In approximately 15 to 30 percent of people, urushiol does not initiate any immune system response at all, while at least 25% of people have very strong immune responses resulting in severe symptoms [4]. In addition to direct contact with the plant, transmission of the oil can occur by touching contaminated items (for example clothing, gloves, or tools) or animals, particularly pets. When poison oak is burned, the oils can disperse via the smoke particles. Breathing this smoke can cause severe respiratory irritation requiring immediate medical attention [2]. The name urushiol comes from the Japanese word "urushi," which is the Japanese name for Toxicodendron vernicifluum, or Chinese lacquer tree. The oxidation and polymerization of urushiol in the tree's sap in the presence of moisture allows it to form a hard lacquer, which is used to produce traditional Chinese, Korean and Japanese lacquerware [5]. As the substance is poisonous to the touch until it dries, the creation of lacquerware has long been practiced only by skilled dedicated artisans [6]. The skin rash resulting from exposure to urushiol is most often an itchy, red rash with bumps or blisters, appearing 1-2 days after exposure. The rash usually lasts 1 to 3 weeks, although may last longer in severe cases. Although painful and awful looking, the rash is typically not life-threatening and typically does not require medical attention. However, if you develop any of these symptoms, you should go to the emergency room right away [7]:

If you have a serious reaction, you will likely need prescription medicine. Your doctor may prescribe a steroid ointment or oral steroid medication such as prednisone. If you have an infection, your doctor may prescribe an antibiotic. You may have an infection if you develop a fever or have pus, pain, swelling, and warmth around the rash [8]. Contrary to popular belief, the skin reaction is not directly caused by the urushiol oil burning or poisoning your skin. Instead, the oil "tricks" your immune system into attacking your own skin cells as if they were foreign invaders! The mechanism for this is as follows. After skin exposure occurs, urushiols are oxidized in the body. The oxidized urushiols chemically react with and change the shape of integral membrane proteins on exposed skin cells. The affected proteins interfere with the immune system's ability to recognize these cells as normal parts of the body. This causes an immune response towards the complex of urushiol derivatives bound in the skin proteins, attacking the skin cells as if they were foreign bodies [5]. If you do come in contact with poison oak, it is important to wash the exposed skin right away. Time is of the essence, as 50% of urushiol can be absorbed within 10 minutes [5]. It is also important to wash your clothing and any other items that may have come in contact with the poison oak such as shoes, backpacks, hats, etc. Remember, however, that the only full-proof way to prevent poison oak rashes is to avoid coming in contact with the plant and its oils in the first place, which means learning how to identify and avoid poison oak. |

Identifying and avoiding poison oak

Identification of poison oak is complicated by the fact that its appearance changes depending upon the time of year and the location where it is growing. In the spring, summer, or fall the easiest way to identify poison oak is using the old saying: "Leaves of three, let it be!" Poison oak leaves normally consist of three leaflets with the stalk of the central leaflet being longer than those of the other two. (Note that what you may think of as a "leaf" is technically a "leaflet." A "leaf" consists of a group of three "leaflets.") Even though leaflets are almost always in groups of three, leaves are occasionally comprised of 5, 7, or 9 leaflets. Poison oak leaves (groups of leaflets) alternate along the stem. Each leaflet is 1 to 4 inches long and smooth with toothed or lobed edges. The diversity in leaf size and shape accounts for the Latin term diversilobum in the species name. The surface of the leaves can be glossy or dull and sometimes even somewhat hairy, especially on the lower surface [2].

|

Poison oak leaves are often confused with true oak leaves which can look similar; however, true oak leaves grow singly, not in groups [2]. Another common plant confused with poison oak is wild blackberry. The way to tell them apart is that wild blackberry vines have thorns on them, while poison oak stems are smooth [9]. Also, wild blackberry produces edible and easily distinguishable black berries in the summer, while poison oak produces bunches of tiny white or cream colored berries.

Poison oak grows in different forms, depending upon the location and environment. In open areas under full sunlight, it forms a dense, leafy shrub usually 1 to 6 feet high. In shaded areas, such as in coastal redwoods and oak woodlands, it grows as individual or groups of stalks, or as a climbing vine, supporting itself on other vegetation or upright objects using its aerial roots [2]. The vines can grow to over 100 feet long with a trunk diameter of up to 8 inches [10]. When you are out on the trails in in Northern California, it is not uncommon to see multiple variations of poison oak during one day. For example, Point Reyes is an excellent place to see poison oak shrubs in exposed areas along the coast, and poison oak stalks and vines in the dense forests in the coastal hills. This means that you not only need to avoid plants growing on the ground, but also vines that may be hanging down from the trees above! The appearance of poison oak also changes depending upon the season. In the spring, tiny crimson or rust-colored leaves emerge and quickly turn a vibrant green. Also in the spring poison oak produces small, white-green flowers at the point where leaves attach to the stem. In the summer, poison oak leaves are a vibrant green and may be dull or glossy. Whitish-green, round fruit form in late summer. In the fall, the leaves turn attractive shades of orange and red, and later turn brown and fall to the ground. The most difficult time to identify poison oak is in the winter when the stalks and vines are bare. In this case, the easiest way to identify poison oak is by the presence of the brown leaves on the ground. Also, the branching of poison oak stalks is very regular compared to the haphazard branching of many other types of shrubs. Poison oak vines can be identified by the hairy aerial roots that attach it to the tree. In Northern California, many of the vines you see growing up the trunks of trees in forests are actually poison oak. Just because there are no leaves doesn't mean that plant is harmless! Every part of the plant contains urushiol and can cause a rash with exposure [2],[4]. In fact, the most severe reaction I have had was due to breaking bare poison oak stalks to clear a trail in the winter. Since there were no leaves on the stalks I had no idea it was poison oak! |

|

Urushiol-blocking creams containing the ingredient bentoquatam can reduce your risk of getting a rash if exposed to poison oak. The most popular of these creams was IvyBlock [11], but for some reason is now discontinued. These creams are applied to the skin before exposure and absorb the urushiol oil before it reaches your skin. These creams do help, but are not 100% effective. In a study done at Duke University Medical Center, seven different barrier creams were evaluated for protection against experimentally produced Toxicodendron rashes [12]. The percent reductions in rash severity per day of assessment were as follows: Stokogard, 59%; Hollister Moisture Barrier, 52%; Hydropel, 48%; Ivy Shield, 22%; Shield Skin, 13%; Dermofilm, 13%; and Uniderm, −9%. So, at best these cremes reduced your risk by about half.

Washing after exposure to poison oak

If you do come in contact with poison oak, it is important to wash the exposed skin right away. Time is of the essence, as 50% of urushiol can be absorbed within 10 minutes [5]. Even washing within the first few hours will limit the severity of the rash. The urushiol can be removed from the skin with rubbing alcohol or alcohol wipes, specialized washes such as Tecnu [13], degreasing soap such as dishwashing soap or detergent, and lots of cool or lukewarm water [3]. Hot water should not be used to wash the skin as it may open the pores to let the oil in [14]. After washing with rubbing alcohol or soap be sure to avoid further exposure that day, since these products also will remove your skin’s protective oils which help guard against urushiol absorption. Your body will require 3-6 hours to regenerate these protective oils [2].

|

Clothing, shoes, or other items that have come in contact with the oil should be washed thoroughly with soap and warm or hot water. If not thoroughly removed, urushiol can remain potent for years. A study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in 1941 found that urushiol extracted from poison ivy and stored in a jar was still potent after five years, contaminated cloth samples were potent after storage for a year, and cut branches laid out in the sun were still potent after eighteen months [15]. So, if you put away a contaminated jacket without washing it and take it out a year later, the oil on the jacket may still cause a reaction [16]. Don't forget that urushiol oils may also hide in your car! When you get into your car after a run or hike, any oils on your hands or clothing can be transferred to the door handle, seat, steering wheel, seat belt, and anything else you touch. To prevent this, I find that it is best to wash your hands or wipe them with alcohol wipes before getting in the car. Also, change your clothes or put down a towel on your seat before getting in. Don't forget to immediately throw that towel in the wash when you get home!

Many people say that Tecnu is the best specialized wash for removing urushiol and, in fact, the effectiveness was confirmed in a University of Missouri School of Medicine study comparing a surfactant (Dial ultra dishwashing soap), an oil-removing compound (Goop), and Technu [17]. In this study, the authors concluded "Our study showed 70%, 61.8%, and 56.4% protection with Tecnu, Goop, and Dial, respectively, when compared to the positive control, or to the possible maximum response." Personally, I have used Dawn dishwashing detergent for years with good results; however, I have not found any studies done on the effectiveness of Dawn for removing urushiol. |

Treating a poison oak rash

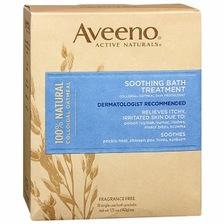

Up to this point the information about poison oak has been fairly straightforward. However, when it comes to the topic of treating a poison oak rash, the information becomes a little more dicey. From steroid pills to hydrocortisone creams, hot showers to ice packs, oatmeal baths to mud masks, cucumber slices to banana peels, it seems that everyone has their own idea of the best way to beat the rash. In this section I have tried to weed out the questionable home remedies from those recommended by reputable sources, such as the Mayo Clinic and American Academy of Dermatology.

Poison oak treatments are usually limited to self-care methods, and the rash typically goes away on its own within two or three weeks [16]. However, If the rash is widespread or results in a large number of blisters, you should seek medical care. Your doctor may prescribe an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone or dexamethasone. If a bacterial infection has developed at the rash site, your doctor will likely give you a prescription for an oral antibiotic.

Poison oak treatments are usually limited to self-care methods, and the rash typically goes away on its own within two or three weeks [16]. However, If the rash is widespread or results in a large number of blisters, you should seek medical care. Your doctor may prescribe an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone or dexamethasone. If a bacterial infection has developed at the rash site, your doctor will likely give you a prescription for an oral antibiotic.

|

The following summarizes the recommended self-care for a poison oak reaction according to the American Academy of Dermatology [7],[8] and the Mayo Clinic [16]:

In addition to the doctor-recommended treatments, there are a plethora of other home remedies, ranging from the benign to the absurd. If you spend even a few minutes browsing the web you will come across all kinds of wacko treatments for poison oak. Here are some other common "treatments" that you may come across.

|

Common poison oak myths... True or false?

Myth 1: The urushiol oil is only found in the leaves

FALSE. Every part of the plant, including the roots, stems, and leaves contains urushiol and can cause a rash with exposure [2],[4].

Myth 2: You can't get a poison oak rash simply from brushing up against the plant

FALSE. The oil is typically found inside the resin canals only. However, it can easily get on the plant surfaces if leaves and stems are bruised or cut, or attacked by chewing/sucking insects. In this case, the sap does leak to the surface of the plant. So, while poison oak exposures due to cutting or damaging the plant are typically more severe, it is still possible that there is enough oil on the surface of the plant to cause a reaction just by brushing up against it [5],[22].

Myth 3: Poison oak is only found close to the ground

FALSE. While poison oak does grow out of the ground, it often grows as a climbing vine, supporting itself on other vegetation or upright objects using its aerial roots [2]. The vines can grow to over 100 feet long with a trunk diameter of up to 8 inches [10]. These vines can hang down from trees and directly contact your torso or face as you pass by.

Myth 4: Rubbing a "poison oak block" cream on your skin beforehand will prevent you from getting a rash

FALSE. Urushiol oil blocking creams and lotions have been found to reduce your risk of rash, but are not 100% effective. In a study done at Duke University Medical Center, seven different barrier creams were evaluated for protection against experimentally produced Toxicodendron rashes [12]. The percent reductions in rash severity per day of assessment were as follows: Stokogard, 59%; Hollister Moisture Barrier, 52%; Hydropel, 48%; Ivy Shield, 22%; Shield Skin, 13%; Dermofilm, 13%; and Uniderm, −9%. So, at best these cremes reduced your risk by about half.

Myth 5: Washing immediately after exposure will prevent a rash

FALSE. While it is important to wash as soon as possible to limit the severity of the rash, 50% of urushiol can be absorbed within 10 minutes [5]. For this reason washing reduces your likelihood of a bad rash but does not prevent it. The only 100% effective way to avoid poison oak rashes is to avoid the oils in the first place.

Myth 6: Using Technu is the only way to remove the oil from the skin

FALSE. Technu [13] has shown to be somewhat more effective than other soaps and cleansers at removing urushiol. This was confirmed in University of Missouri School of Medicine study comparing a surfactant (Dial ultra dishwashing soap), an oil-removing compound (Goop), and Technu [17]. In this study, the authors concluded "Our study showed 70%, 61.8%, and 56.4% protection with Tecnu, Goop, and Dial, respectively, when compared to the positive control, or to the possible maximum response." So while Technu does a good job removing the oil, other types of soaps and cleansers can do an adequate job as well, as long as you use plenty of water.

Myth 7: The oil breaks down in a few days anyway, so you don't need to wash your contaminated gear

FALSE. If not thoroughly removed from objects, urushiol can remain potent for years. A study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in 1941 found that urushiol extracted from poison ivy and stored in a jar was still potent after five years, contaminated cloth samples were potent after storage for a year, and cut branches laid out in the sun were still potent after eighteen months [15]. So, if you put away a contaminated jacket without washing it and take it out a year later, the oil on the jacket may still cause a reaction [16].

Myth 8: The fluid in the skin blisters contains the oil, so scratching and releasing the fluid will spread the rash

FALSE. A poison ivy rash itself isn't contagious. Blister fluid doesn't contain urushiol and won't spread the rash. In addition, you can't get poison ivy from another person unless you've had contact with urushiol that's still on that person or on his or her clothing [16].

Myth 9: Scrubbing and breaking the blisters open actually helps the rash heal

FALSE. Actually the opposite is true; breaking the blisters can delay healing and lead to infection [7].

Myth 10: Holding the affected skin under scalding hot water is a good way to eliminate itching for hours

TRUE? Apparently this depletes your body’s supply of itch-causing histamines and can give you relief for a few hours. While this does seem to work, it also seems to make the rash redder and more swollen. I was not able to find any definitivie answers as to whether this one is a good idea or not.

Myth 11: Dabbing the rash with household bleach will help it to "dry up" and heal faster

FALSE. This is not recommended by reputable sources. In fact, Maryland Primary Care Physicians recommends against this, saying that "any caustic material, such as bleach or rubbing alcohol, can damage your tissues and make it harder for a wound to heal [21]."

Myth 12: I'm not allergic to poison oak!

FALSE. Just because you haven't gotten rashes in the past, doesn't mean that you are forever immune. Since the skin reaction is an allergic one, people may develop progressively stronger reactions after repeated exposures, or show no immune response on their first exposure, but show sensitivity on following exposures [4].

Myth 13: Asians are immune to poison oak

TRUE? Actually, there is some evidence suggesting that native-born Hawaiians and Asians may be less susceptible to poison oak, possibly due to early exposure to mangoes and Japanese lacquer which contain urushiol oil [23].

Myth 14: With repeated exposures you can become immune

FALSE. In fact, just the opposite is true. Some people are not sensitive but may become sensitive after repeated exposure [24]. Also, since the skin reaction is an allergic one, people may actually develop progressively stronger reactions after repeated exposures [4].

Myth 15: Eating poison oak leaves/berries/oil can make you immune

TRUE? (But please don't try it) It is reported that some Native American peoples made infusions of dried roots, or ate the buds in the spring, to develop an immunity from poison oak reactions [25]. Also, a study performed in 1982 on twenty-one adults, highly sensitive to urushiol, showed that their sensitivity was significantly reduced after ingesting up to 300 mg of urushiol over three to six months [26]. Retesting of the subjects after three months showed that this reduction in sensitivity remained even after the subjects stopped ingesting the urushiol! And it seems one man is putting this to practice. A man named Jack Elliott claims that each spring he picks newly sprouted poison oak leaves and eats them. He claims that his reaction has become increasingly milder until it was essentially non-existent. He further claims that he never once broke out in a rash from eating poison oak or suffered any adverse consequences [27].

FALSE. Every part of the plant, including the roots, stems, and leaves contains urushiol and can cause a rash with exposure [2],[4].

Myth 2: You can't get a poison oak rash simply from brushing up against the plant

FALSE. The oil is typically found inside the resin canals only. However, it can easily get on the plant surfaces if leaves and stems are bruised or cut, or attacked by chewing/sucking insects. In this case, the sap does leak to the surface of the plant. So, while poison oak exposures due to cutting or damaging the plant are typically more severe, it is still possible that there is enough oil on the surface of the plant to cause a reaction just by brushing up against it [5],[22].

Myth 3: Poison oak is only found close to the ground

FALSE. While poison oak does grow out of the ground, it often grows as a climbing vine, supporting itself on other vegetation or upright objects using its aerial roots [2]. The vines can grow to over 100 feet long with a trunk diameter of up to 8 inches [10]. These vines can hang down from trees and directly contact your torso or face as you pass by.

Myth 4: Rubbing a "poison oak block" cream on your skin beforehand will prevent you from getting a rash

FALSE. Urushiol oil blocking creams and lotions have been found to reduce your risk of rash, but are not 100% effective. In a study done at Duke University Medical Center, seven different barrier creams were evaluated for protection against experimentally produced Toxicodendron rashes [12]. The percent reductions in rash severity per day of assessment were as follows: Stokogard, 59%; Hollister Moisture Barrier, 52%; Hydropel, 48%; Ivy Shield, 22%; Shield Skin, 13%; Dermofilm, 13%; and Uniderm, −9%. So, at best these cremes reduced your risk by about half.

Myth 5: Washing immediately after exposure will prevent a rash

FALSE. While it is important to wash as soon as possible to limit the severity of the rash, 50% of urushiol can be absorbed within 10 minutes [5]. For this reason washing reduces your likelihood of a bad rash but does not prevent it. The only 100% effective way to avoid poison oak rashes is to avoid the oils in the first place.

Myth 6: Using Technu is the only way to remove the oil from the skin

FALSE. Technu [13] has shown to be somewhat more effective than other soaps and cleansers at removing urushiol. This was confirmed in University of Missouri School of Medicine study comparing a surfactant (Dial ultra dishwashing soap), an oil-removing compound (Goop), and Technu [17]. In this study, the authors concluded "Our study showed 70%, 61.8%, and 56.4% protection with Tecnu, Goop, and Dial, respectively, when compared to the positive control, or to the possible maximum response." So while Technu does a good job removing the oil, other types of soaps and cleansers can do an adequate job as well, as long as you use plenty of water.

Myth 7: The oil breaks down in a few days anyway, so you don't need to wash your contaminated gear

FALSE. If not thoroughly removed from objects, urushiol can remain potent for years. A study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology in 1941 found that urushiol extracted from poison ivy and stored in a jar was still potent after five years, contaminated cloth samples were potent after storage for a year, and cut branches laid out in the sun were still potent after eighteen months [15]. So, if you put away a contaminated jacket without washing it and take it out a year later, the oil on the jacket may still cause a reaction [16].

Myth 8: The fluid in the skin blisters contains the oil, so scratching and releasing the fluid will spread the rash

FALSE. A poison ivy rash itself isn't contagious. Blister fluid doesn't contain urushiol and won't spread the rash. In addition, you can't get poison ivy from another person unless you've had contact with urushiol that's still on that person or on his or her clothing [16].

Myth 9: Scrubbing and breaking the blisters open actually helps the rash heal

FALSE. Actually the opposite is true; breaking the blisters can delay healing and lead to infection [7].

Myth 10: Holding the affected skin under scalding hot water is a good way to eliminate itching for hours

TRUE? Apparently this depletes your body’s supply of itch-causing histamines and can give you relief for a few hours. While this does seem to work, it also seems to make the rash redder and more swollen. I was not able to find any definitivie answers as to whether this one is a good idea or not.

Myth 11: Dabbing the rash with household bleach will help it to "dry up" and heal faster

FALSE. This is not recommended by reputable sources. In fact, Maryland Primary Care Physicians recommends against this, saying that "any caustic material, such as bleach or rubbing alcohol, can damage your tissues and make it harder for a wound to heal [21]."

Myth 12: I'm not allergic to poison oak!

FALSE. Just because you haven't gotten rashes in the past, doesn't mean that you are forever immune. Since the skin reaction is an allergic one, people may develop progressively stronger reactions after repeated exposures, or show no immune response on their first exposure, but show sensitivity on following exposures [4].

Myth 13: Asians are immune to poison oak

TRUE? Actually, there is some evidence suggesting that native-born Hawaiians and Asians may be less susceptible to poison oak, possibly due to early exposure to mangoes and Japanese lacquer which contain urushiol oil [23].

Myth 14: With repeated exposures you can become immune

FALSE. In fact, just the opposite is true. Some people are not sensitive but may become sensitive after repeated exposure [24]. Also, since the skin reaction is an allergic one, people may actually develop progressively stronger reactions after repeated exposures [4].

Myth 15: Eating poison oak leaves/berries/oil can make you immune

TRUE? (But please don't try it) It is reported that some Native American peoples made infusions of dried roots, or ate the buds in the spring, to develop an immunity from poison oak reactions [25]. Also, a study performed in 1982 on twenty-one adults, highly sensitive to urushiol, showed that their sensitivity was significantly reduced after ingesting up to 300 mg of urushiol over three to six months [26]. Retesting of the subjects after three months showed that this reduction in sensitivity remained even after the subjects stopped ingesting the urushiol! And it seems one man is putting this to practice. A man named Jack Elliott claims that each spring he picks newly sprouted poison oak leaves and eats them. He claims that his reaction has become increasingly milder until it was essentially non-existent. He further claims that he never once broke out in a rash from eating poison oak or suffered any adverse consequences [27].

References

[1] Toxicodendron. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxicodendron. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[2] J. M. DiTomaso and W. T. Lanini. Poison Oak. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources UC-IPM online. Available at http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PDF/PESTNOTES/pnpoisonoak.pdf. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[3] "Poisonous Plants." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) online article. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/plants/. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[4] Urushiol-induced contact dermatitis. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urushiol-induced_contact_dermatitis. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[5] Urushiol. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urushiol. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[6] Japanese lacquerware. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_lacquerware. Accessed Dec. 21, 2014.

[7] "Poison ivy: Tips for treating and preventing." American Academy of Dermatology online article. Available at

https://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/diseases-and-treatments/m---p/poison-ivy/tips. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[8] "Poison ivy: Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome." American Academy of Dermatology online article. Available at

https://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/diseases-and-treatments/m---p/poison-ivy/diagnosis-treatment. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[9] S. J. Baker. The Sure-Fire Poison Oak & Poison Ivy Identification System. Coleman Creek Press, 2012. Available at http://www.poisonoakandpoisonivy.com/Resources/Sure-Fire.%20ONLINE%20%20with%20cover%20copy.pdf. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[10] Toxicodendron diversilobum. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxicodendron_diversilobum. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[11] http://www.ivyblock.com

[12] S.A. Grevelink, D.F. Murrell, and E.A. Olsen. "Effectiveness of various barrier preparations in preventing and/or ameliorating experimentally produced Toxicodendron dermatitis." J Amer Acad Dermatol. 27.2.1 (1992) 182-188.

[13] Available from Tec Labs. http://www.teclabsinc.com

[14] "Skin Care: Poison Ivy, Sumac, and Oak." Princeton University online article. Available at http://www.princeton.edu/uhs/healthy-living/hot-topics/skin-care/. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[15] B. Shelmire. "The poison ivy plant and its oleoresin." J Invest Dermatol. 4.5 (1941) 337-348. Available at http://www.nature.com/jid/journal/v4/n5/pdf/jid194134a.pdf. Accessed Dec. 21, 2014.

[16] "Diseases and Conditions: Poison Ivy Rash." Mayo Clinic online article. Available at http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/poison-ivy/basics/prevention/con-20025866. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[17] A.S. Stibich, M. Yagan, V. Sharma, B. Herndon, and C. Montgomery. "Cost-effective post-exposure prevention of poison ivy dermatitis." Int J Dermatol. 39.7 (2000) 515-8.

[18] Calamine. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calamine. Accessed Dec. 27, 2014.

[19] (i) D. Long, N.H. Ballentine, J.G. Marks Jr. "Treatment of poison ivy/oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed." Am J Contact Dermat. 8.3 (1997) 150-3. (ii) M.V. Abrams, C.P. Bowers, Y.L Mull, D.H. Kinder. "The effectiveness of jewelweed, Impatiens capensis, the related cultivar I. balsamina and the component, lawsone in preventing post poison ivy exposure contact dermatitis." J Ethnopharmacol. 143.1 (2012) 314-8.

[20] "Poison Ivy and Poison Oak." Healthcentral.com online article. Available at http://www.healthcentral.com/encyclopedia/408/395.html. Accessed Dec. 28, 2014.

[21] J. Harms. "No Bleach Please: How to Treat Poison Ivy." Maryland Primary Care Physicians online article. Available at

http://www.mpcp.com/articles/no-bleach-please-how-to-treat-poison-ivy. Accessed Dec. 27, 2014.

[22] W.P. Armstrong and W.L. Epstein. "Poison Oak: More Than Just Scratching The Surface." Herbalgram (American Botanical Council). 34 (1995) 36-42.

[23] E.R. Claiborne and E. Epstein. "Racial and environmental factors in susceptibility to Rhus." AMA Arch Derm. 75.2 (1957) 197-201.

[24] S.P Brown and P. Grace. "Identification of Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, Poison Sumac, and Poisonwood." University of Florida Extension online article. Available at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/EP/EP22000.pdf. Accessed Dec 20, 2014.

[25] Native American Ethnobotany Database: Toxicodendron diversilobum. Univ. of Michigan, Dearborn. Available at http://herb.umd.umich.edu/herb/search.pl?searchstring=Toxicodendron+diversilobum. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[26] W.L. Epstein, V.S. Byers, W. Frankart. "Induction of Antigen Specific Hyposensitization to Poison Oak in Sensitized Adults." Arch Dermatol. 118.9 (1982) 630-633.

[27] "Eating Poison Oak." Online article from Jack Elliott's Santa Barbara Adventure blog. Available at http://yankeebarbareno.com/2011/03/03/eating-poison-oak. Accessed Dec. 21, 2014.

[2] J. M. DiTomaso and W. T. Lanini. Poison Oak. University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources UC-IPM online. Available at http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PDF/PESTNOTES/pnpoisonoak.pdf. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[3] "Poisonous Plants." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) online article. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/plants/. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[4] Urushiol-induced contact dermatitis. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urushiol-induced_contact_dermatitis. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[5] Urushiol. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Urushiol. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[6] Japanese lacquerware. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_lacquerware. Accessed Dec. 21, 2014.

[7] "Poison ivy: Tips for treating and preventing." American Academy of Dermatology online article. Available at

https://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/diseases-and-treatments/m---p/poison-ivy/tips. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[8] "Poison ivy: Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome." American Academy of Dermatology online article. Available at

https://www.aad.org/dermatology-a-to-z/diseases-and-treatments/m---p/poison-ivy/diagnosis-treatment. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[9] S. J. Baker. The Sure-Fire Poison Oak & Poison Ivy Identification System. Coleman Creek Press, 2012. Available at http://www.poisonoakandpoisonivy.com/Resources/Sure-Fire.%20ONLINE%20%20with%20cover%20copy.pdf. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[10] Toxicodendron diversilobum. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toxicodendron_diversilobum. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[11] http://www.ivyblock.com

[12] S.A. Grevelink, D.F. Murrell, and E.A. Olsen. "Effectiveness of various barrier preparations in preventing and/or ameliorating experimentally produced Toxicodendron dermatitis." J Amer Acad Dermatol. 27.2.1 (1992) 182-188.

[13] Available from Tec Labs. http://www.teclabsinc.com

[14] "Skin Care: Poison Ivy, Sumac, and Oak." Princeton University online article. Available at http://www.princeton.edu/uhs/healthy-living/hot-topics/skin-care/. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[15] B. Shelmire. "The poison ivy plant and its oleoresin." J Invest Dermatol. 4.5 (1941) 337-348. Available at http://www.nature.com/jid/journal/v4/n5/pdf/jid194134a.pdf. Accessed Dec. 21, 2014.

[16] "Diseases and Conditions: Poison Ivy Rash." Mayo Clinic online article. Available at http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/poison-ivy/basics/prevention/con-20025866. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[17] A.S. Stibich, M. Yagan, V. Sharma, B. Herndon, and C. Montgomery. "Cost-effective post-exposure prevention of poison ivy dermatitis." Int J Dermatol. 39.7 (2000) 515-8.

[18] Calamine. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calamine. Accessed Dec. 27, 2014.

[19] (i) D. Long, N.H. Ballentine, J.G. Marks Jr. "Treatment of poison ivy/oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed." Am J Contact Dermat. 8.3 (1997) 150-3. (ii) M.V. Abrams, C.P. Bowers, Y.L Mull, D.H. Kinder. "The effectiveness of jewelweed, Impatiens capensis, the related cultivar I. balsamina and the component, lawsone in preventing post poison ivy exposure contact dermatitis." J Ethnopharmacol. 143.1 (2012) 314-8.

[20] "Poison Ivy and Poison Oak." Healthcentral.com online article. Available at http://www.healthcentral.com/encyclopedia/408/395.html. Accessed Dec. 28, 2014.

[21] J. Harms. "No Bleach Please: How to Treat Poison Ivy." Maryland Primary Care Physicians online article. Available at

http://www.mpcp.com/articles/no-bleach-please-how-to-treat-poison-ivy. Accessed Dec. 27, 2014.

[22] W.P. Armstrong and W.L. Epstein. "Poison Oak: More Than Just Scratching The Surface." Herbalgram (American Botanical Council). 34 (1995) 36-42.

[23] E.R. Claiborne and E. Epstein. "Racial and environmental factors in susceptibility to Rhus." AMA Arch Derm. 75.2 (1957) 197-201.

[24] S.P Brown and P. Grace. "Identification of Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, Poison Sumac, and Poisonwood." University of Florida Extension online article. Available at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/EP/EP22000.pdf. Accessed Dec 20, 2014.

[25] Native American Ethnobotany Database: Toxicodendron diversilobum. Univ. of Michigan, Dearborn. Available at http://herb.umd.umich.edu/herb/search.pl?searchstring=Toxicodendron+diversilobum. Accessed Dec. 20, 2014.

[26] W.L. Epstein, V.S. Byers, W. Frankart. "Induction of Antigen Specific Hyposensitization to Poison Oak in Sensitized Adults." Arch Dermatol. 118.9 (1982) 630-633.

[27] "Eating Poison Oak." Online article from Jack Elliott's Santa Barbara Adventure blog. Available at http://yankeebarbareno.com/2011/03/03/eating-poison-oak. Accessed Dec. 21, 2014.